Before going into my review, I would like to stress that I went into Miyazaki’s newest film completely blind, in no small part due to Studio Ghibli’s ingenious choice to release next to no trailers. All I knew going in was that there was a boy, a heron, and not much else. I would strongly recommend anyone wishing to view the film stop reading this review and watch the movie. More than any piece of media I have experienced, this film works best going into it blind to be taken along its winding journey.

Now onto the spoilers for anyone who dares (or has already watched the movie)—the basic premise is as follows: young boy Mahito moves to the Japanese countryside during the height of WW2 along with his father. His mother has died in a fire in Tokyo, implied to be from firebombings, and Mahito’s father has remarried his late wife’s sister and now Mahito’s stepmother, Natsuko.

The opening scene depicts that event, as Mahito and his father wake up in the early part of the morning to discover the hospital where his mother is in flames. It becomes such a kinetic and frantic scene that it is still seared in my mind even as I write this, Mahito moving with such energy while the world around him and even the camera grow into an increasing blur. Except the blur is actually the raging fire around Mahito. It haunts him in his dreams, and the clarity the animation lacks represents his own unclear and conflicted attitude. Once the film returns briefly to this scene after the opening act, it is undoubtedly one of the most visually impressive scenes I have ever witnessed.

Visually, Miyazaki is still at the top of his game, and while most of the movie is painstakingly animated by hand, it still uses some 3D elements which will certainly age better than some of Studio Ghibli’s previous forays in 3D animation. It also maintains the style his films are known for, but further polished and clean after nearly a decade since his last film. Thus it maintains a distinct style compared to Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume, released earlier this year, and other similar works.

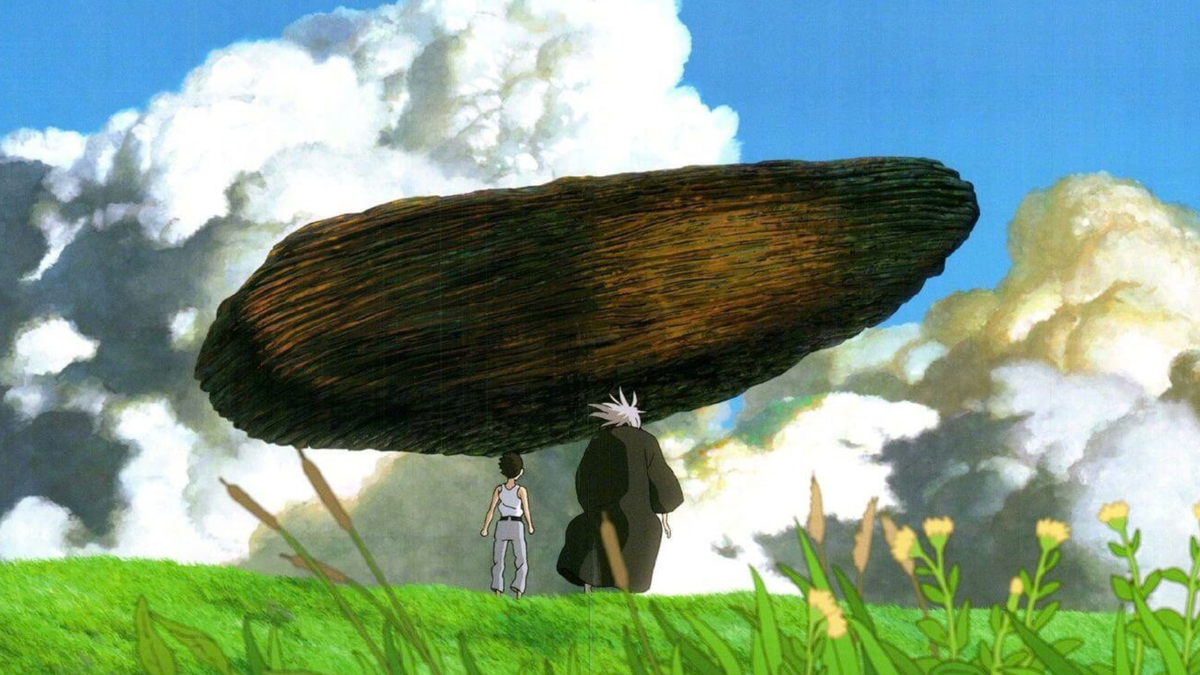

Yet audiences will be surprised to find how the story remains relatively grounded for much of its runtime. Mahito may be a boy, but the film spends plenty of time on his emotional trauma and how he settles into Natsuko’s ancestral home full of pampering maids. The truly fantastical elements begin at around the halfway point in the story, and plunge Mahito into a world as beautiful as any other Miyazaki film. There is undoubtedly something unnatural about it, the tower looming ominously below in the dead world and above in the real. It hints toward the ultimate artifice of this world, but this world is nonetheless stunning, from a raging sea where the dead and unborn warawara spirits wander to the medieval elegance of the tower supporting this world and the whimsy, man-eating parakeets that guard it.

Still image from Studio Ghibli

Both of these, the warawara and the human-sized parakeets, are adorable. One of them does just amount to cute white balls with eyes, but the parakeets are something far more glorious, whose goof waddle has them hiding comically large kitchen knives behind them. A common running theme throughout the movies are birds. The parakeets have an imposing, majestic king. Pelicans feature heavily during the middle part of the film. And the clear star among them is the heron himself, whose opening scene sees it sweep across the screen, yet another standout moment. The heron begins as an antagonist, with his bushy nose and creepy grin peering out of the heron’s long mouth to create something unnerving. But as Mahito plunges into the other world, the heron is unmasked and becomes probably the funniest character in the film.

Many of the human characters are goofy and comic reliefs themselves. Mahito’s father is overconfident in himself and too eager. Even when his son has disappeared, he must take extravagant efforts to fully gear up, not unlike Mahito. The maids and runners of the house may be tired and aging, but they can still rally immense energy for canned goods and puffs of tobacco, rare commodities in war.

Mahito himself is an excellent protagonist, who after the opening scene, is almost completely silent and stoic. The early parts of the story make a point of giving him very little dialogue. Mahito is instead defined by the quiet determination of his actions. He valiantly faces the Heron numerous times in the early acts with first a wooden sword, and then a makeshift bow and arrow. Most striking, however, are the cracks in this persona, where Mahito is no longer a stoic and standoffish boy. He cries reading his mother’s final message to him, snuck away in his room. And after being bullied by the children at school, he scars himself with a rock.

The story of the Boy and the Heron concerns itself chiefly with how Mahito comes to accept his world. The choice to set it during wartime Japan highlights this. His world at the start is chaotic and full of malice, where the life of his mother was taken unfairly. The home he finds himself in is unmistakably empty, its old folk only having a memory of brighter days. Mahito perhaps rejects most Natsuko, who is the spitting image of his dead mother. When given the choice, why not continue to reside in this “other” world? But the final trick of the film is to reveal the flimsy foundation on which the world stands—a crude tower of blocks.

My first viewing felt particularly confusing, and there is no easy-to-find message to have when the film ends. But it ends with a treasure trove of ideas that gets more interesting the more they are reflected upon. The Boy and the Heron is more than worthy of Miyazaki’s name.