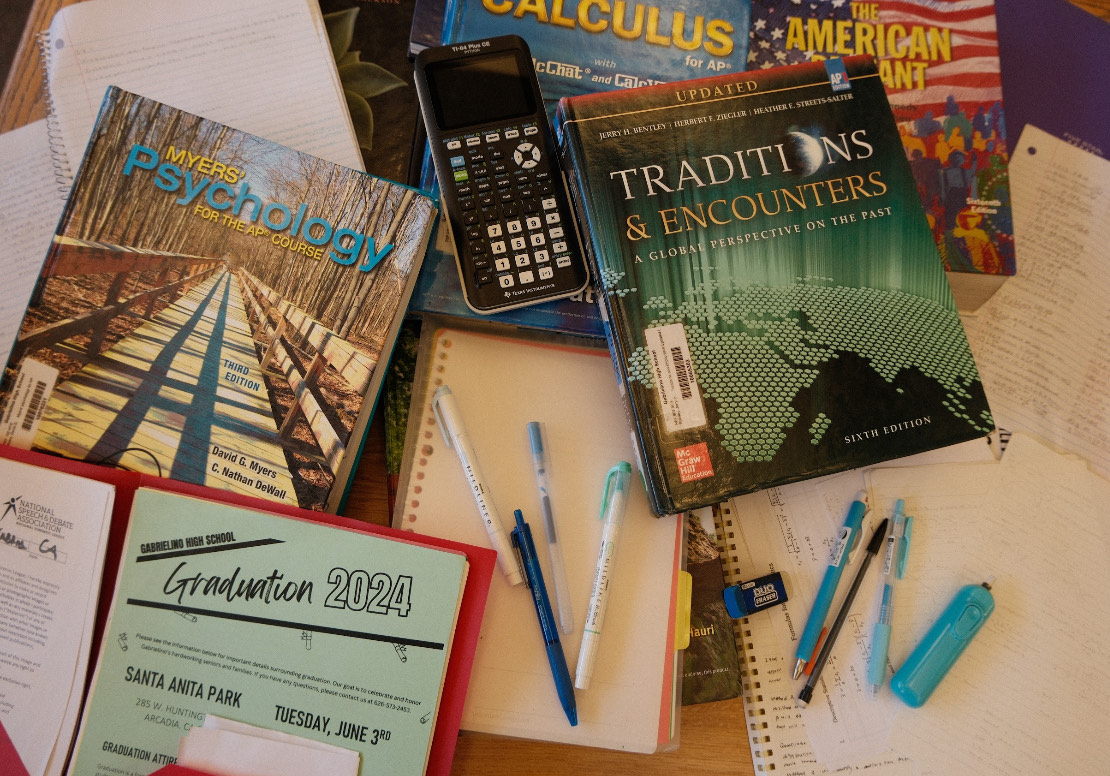

Junior year is often considered the hardest year of high school. Students are inundated with difficult coursework. However, one major task that juniors at Gabrielino High School don’t properly prepare for is state testing. The current lack of preparation for state testing negatively affects students’ performance, ultimately reflecting poorly on Gabrielino’s ability to provide a comprehensive education.

Juniors take two major tests in terms of state standardized testing. The first is the Standard Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC). The second is the California Science Test (CAST).

Together, these tests make up the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP). In 2025, Gabrielino was able to improve by 5 points on the CAST, 7 points on the ELA portion of the SBAC, and 6 points on the math portion of the SBAC. While this is positive, Gabrielino is still scoring considerably lower than pre coronavirus pandemic years.

Students aren’t properly exposed to the structure of the CAASPP, making them less likely to perform well. According to a case study conducted by the California Department of Education, students who were exposed to curriculums with the SBAC in mind scored higher on the actual exam. However, most juniors don’t have this exposure or structure in their classes.

“I didn’t do any prep [for testing]. I was more focused on my classes,” said junior Natalia San Lucas, who tested earlier this year. San Lucas is currently in AP Calculus AB. “When I was in Algebra 2, the teacher started assigning [practice material] the week before.”

Additionally, the culture around state testing is discouraging for students. A study done by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that incentives, or a reason to take the test, greatly improve test scores. These incentives are nonexistent at Gabrielino, where the CAASPP is seen as a less important burden.

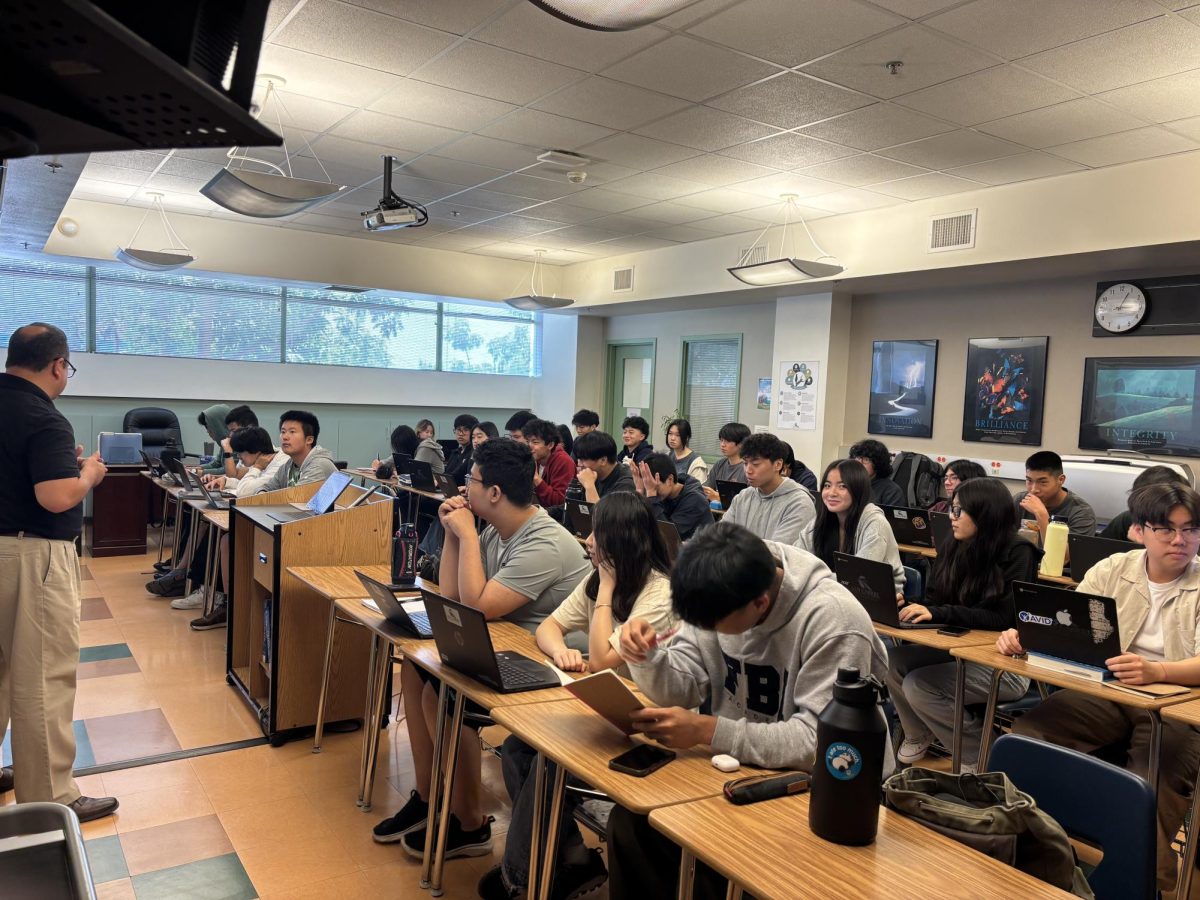

As the head of the math department, math teacher and department chair Jorge Salas has been searching for ways to improve Gabrielino’s state testing scores.

“What do you value more, the AP program or the state testing program,” pointed out Salas. “Students… find more value in the AP program.”

Despite these circumstances, there are ways to improve these scores. Testing prep should be integrated into the curriculum, a goal that the math department is currently working to achieve. Another potential way to improve scores is by giving teachers access to practice modules.

“It’s on [the administrators] to help the teachers and give them access to the modules that break the test down; teachers can be familiar with [the material] and figure out ways to teach it,” described Assistant Principal Kevin Murchie, who was in charge of organizing testing this year.

Students also need to be motivated to take the test. This can include holding a rally before state testing. Murchie also plans to give students their scores before they enter their senior year. This gives students a tangible number to look at after the test is taken.

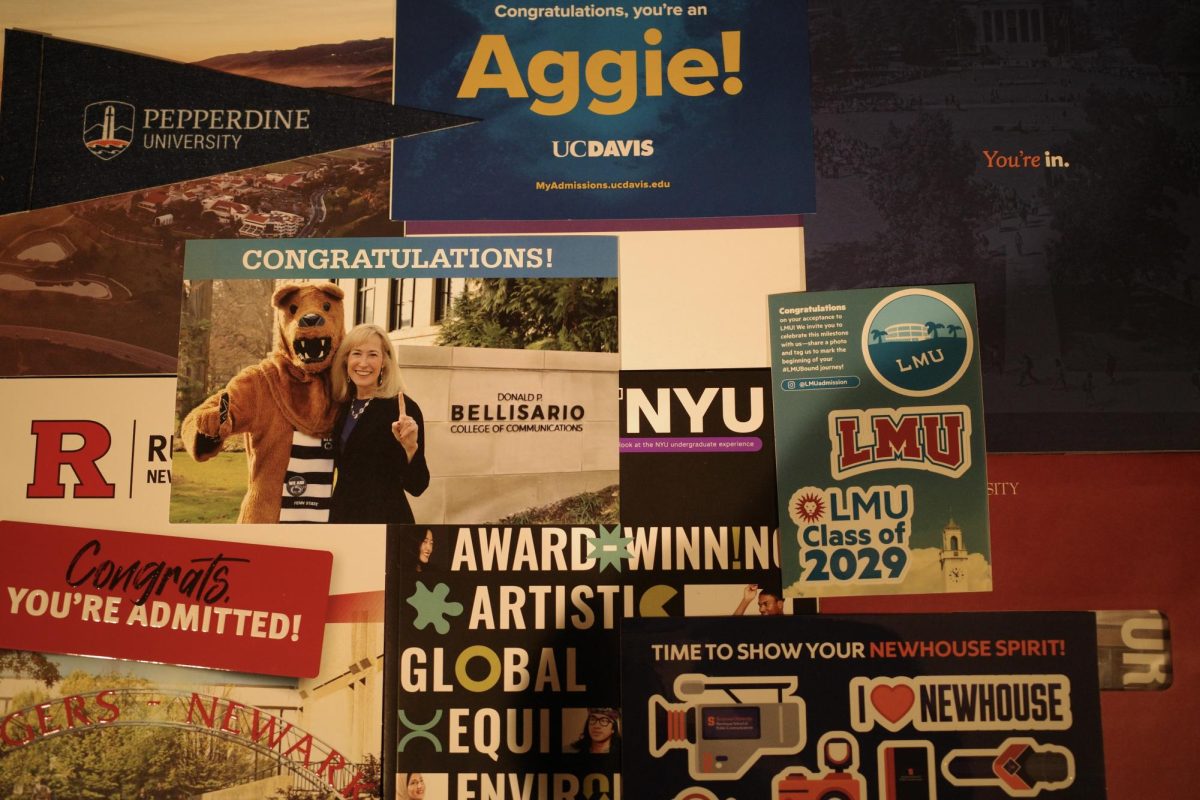

Students should also be told why the tests even matter. Because test scores help gauge the academic rigor of a school, colleges look more favorably at students that go to schools with higher scores on the CAASPP. This means that students’ college prospects can be affected by how well their school scores on state standardized tests.

Gabrielino students have the potential to score much higher on the CAASPP. In order to improve, students will need to be more properly prepared—getting in sufficient practice and becoming more motivated to test. This would both help the school’s image and give students a stronger sense of purpose while taking their final state exam.