The classes are a result of Assembly Bill 101’s mandate for California public and charter high schools to offer an ethnic studies course starting in 2025 and make ethnic studies a graduation requirement for the class of 2029-2030.

Race and Society, taught by Ryan Kammerman, history department, will follow the timeline of United States history with a focus on minority groups and social-emotional learning. Kammerman aims to foster critical thinking about identity, something he explored as a sociology major in college.

“[I want to] incorporate stories that I wasn’t taught in my high school class to provide a more inclusive one that would allow my demographics of my students to feel more connected to US history,” he stated.

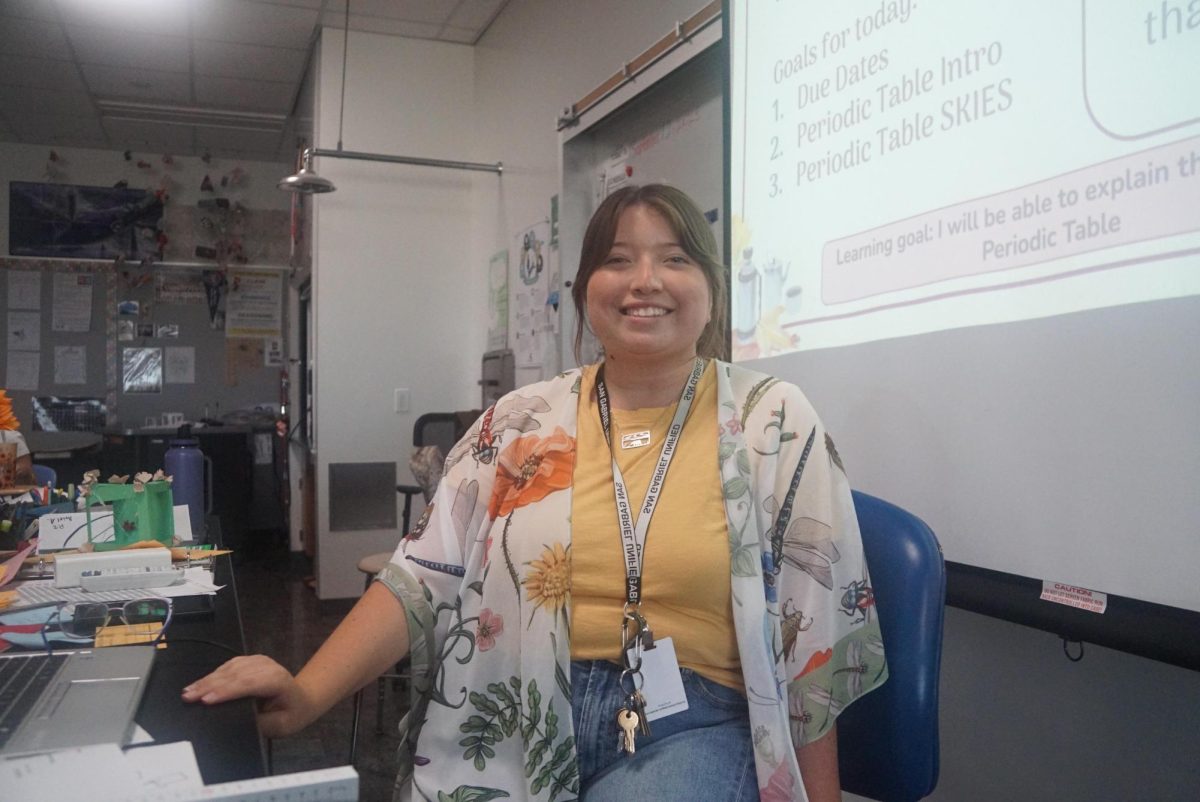

Tera Straker, English department, will be teaching World Literature. The class will read texts and do service-based projects highlighting the experiences of Asian, Latinx, Native, and African Americans.

“I personally am of mixed ethnicity, as are my children, but did not read novels or stories that represented my Asian or Latin background nor did I learn anything about African culture before or after slavery,” said Straker. “It would have been an enriching, engaging experience to have learned about these rich cultures.”

While the teacher for Introduction to Ethnic Studies is still undetermined, the class will encourage social consciousness and create connections to individual and community history.

Like Gabrielino, Del Mar High School will also establish an ethnic studies curriculum. The course, grounded in fine arts, will institutionalize its goals of helping students find their power and pride.

“It’s one thing if it’s your practice, but if you can elevate it to the level of policy, then it’s definitely stronger,” stated Del Mar High School principal Muhammad Abdul-Qawi. “When you do things in a formal way, it just validates it even further.”

Abdul-Qawi’s personal experience in a high school American Minority Culture class changed his path in life. He wants his students to also understand that achieving academically is part of their identity and culture.

“I think if I would have had that earlier in my school life, then I would have known that my academic disengagement wasn’t consistent with the people that I came from,” he stated.

The courses were determined through a committee of teachers, administrators, and students. The committee’s vision was for the classes to foster cultural empathy, empower students, build community and belonging, and embrace identities.

“When you’re older and in APs, there’s not a lot of collaborative work,” said Reyan Nguy, a senior on the ethnic studies commission. “[Ethnic studies could] bring more perspective…more interest in different cultures.”

A key part of the committee’s process was touring Val Verde High School and Azusa High School, which already teach ethnic studies. Committee members found inspiration in observing passionate teachers, high student engagement, and a welcoming community environment.

“It redefined how I thought about ethnic studies,” stated senior Uni Sky, also on the commission, who was originally skeptical about the efficacy of an ethnic studies course. “[When] we went to Val Verde, I saw that the classes weren’t as controversial as they seemed, they were just a more humanized lens to look at history through.”